Summer 2017 Reads

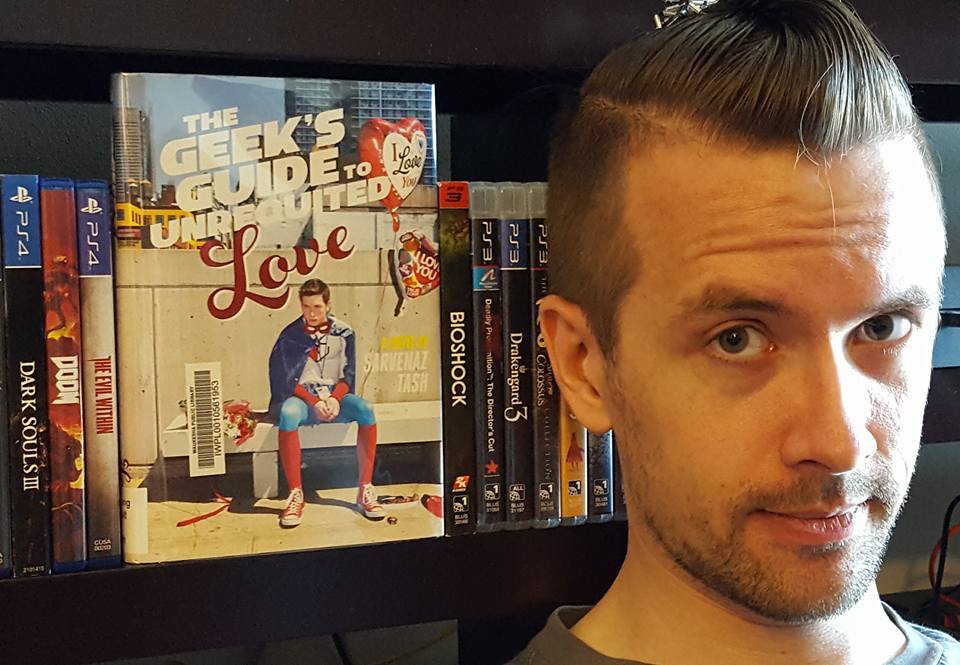

The Geek's Guide to Unrequited Love

by Sarvenaz Tash

My ninth summer 2017 read was The Geek’s Guide to Unrequited Love by Sarvenaz Tash.

Graham is a geek who has recently realized he is in love with his neighbor and best friend Roxy. He figures that a grand gesture at the New York Comic Convention is just the ticket, and as luck would have it, a mutual idol of theirs is breaking decades of silence to visit the con. What follows is a series of setbacks and new plans as Graham desperately attempts to win Roxy’s heart and walk out of the NYCC a champion… or at least with a girlfriend.

I first stumbled upon this book at Barnes and Noble and let’s just say my initial response wasn’t quite generous.

In an apartment full of geeky stuff, I chose the location that is the worst on my back.

This is gonna end in 1 of 2 ways:

— Jonathan C Bruce (@JonathanCBruce) July 1, 2017

1. Graham maintaining a blog about why Roxy is a monster for friendzoning him.

2. Graham murdering Roxy. pic.twitter.com/AlN9Q97kl1

I admit that it was deeply uncharitable. But the reality is that misogyny is very much a problem in what we call nerd culture, so it did not take much to get into a dark mindset. When I thought about it further, though, I thought that I was being unfair by not giving the book a chance. So I decided to check it out of the library and let myself be surprised.

It… did not quite work out like that.

I want to be clear: the writing of the book is solid. The dialogue is natural and the prose is well-done. The problems, then, arise from two chief places: the plot itself and the audience’s point-of-view character.

Generally speaking, the book doesn’t really work as a cohesive narrative structure. While any kind of convention would be a decent host to any number of stories, what Geek’s Guide does is heavily rely upon anecdotes to fill up time. It ends up feeling like a disjointed series of events, made all the more jarring because the overarching plot (GRAHAM LOVE ROXY) is more or less straightforward.

To make matters even worse, the moments away from the convention center are infinitely more interesting and worthwhile. It is here we find out more about the lives of the characters beyond the things they like. There are genuinely sweet moments, like Graham eating dinner with Roxy’s family, that feel natural and beautiful. It’s hard to shake the sense that the geeky trappings of the NYCC are used as a way to simply not engage heavily with scenes of substantial character development; that is to say, that the largely meaningless word ‘geek’ does most of the heavy lifting for the characters’ identities.

Since the plot it so scattered, it is probably best to focus most of the criticism on someone you will no doubt learn to hate as this book goes on: Graham. Told in first person perspective, we are stuck with Graham and his stereotypical nerd-entitlement right from page one. It is very hard not to despise Graham very quickly for any number of reasons: he someone knows about everything that matters (with the exception of My Little Pony), makes it a point to shit on athletics and athletes (including his jock stepbrother, who he makes no qualms about assuming is deeply unintelligent), and spends the first two-thirds of the book resenting any attention Roxy gives anyone else.

Despite this, everyone in the novel just loves Graham. Even Roxy’s newfound romantic suitor goes out of his way to be nice to the whiny, resentful shithead. It must be because Graham has the one superpower that every person who defines themselves solely by the media they consume wants: the ability to reference a criminal into submission. Yes, at one point he screams a line from The Princess Bride to stop a shoplifter. While this may be something that has happened at some point, it just screams of such weird wish fulfillment that it stands out as the most fantastical element of an otherwise grounded novel.

Other examples of Graham’s shittiness include:

• Suggesting Japanese-American Felicia is a ninja (“not just because she’s of Japanese descent, either” (20) Graham says, fumbling the “I’m not racist” defense)

• Convincing Roxy to lie to her parents, only to get mad at her when she lies to her parents without his approval

• Describing Roxy as “exotic” (although he is trying to pin this on Devin in his mind)

• Agreeing to undermine Felicia’s class rank to assuage his male friend’s ego (so, now he’s trying to undercut not one but two girls’ autonomy!)

• Admitting that he has “opinions on things, too, but few of those things are part of what most would consider the real world” (143), because heaven forbid anyone reach the age of 16 without realizing that the world at large affects them when there’s decades-old pop culture to obsess over

Since the book is centered around geek culture, it is important to know Graham’s relationship with it. However, it is never explained or explored in any meaningful context. He just likes things like Star Wars because it’s a thing that ‘nerds’ like: he is a nerd, ergo, he likes these things. In the last 50 pages or so, there’s a shoehorned in theme of Graham wanting the rigid constructs of fiction over unscripted reality, but it comes out of nowhere and ends up highlighting how little we know about Graham and his apparent love for nerdom. Otherwise, Graham’s lack of engagement is used in what could be understood as a plot point: when he and Roxy discover that the fictional comic series, The Chronicles of Althena, that they both love was radically progressive for its time period (early 90s), he swoons over the PERFECT, NEVER WRONG CREATOR: “It’s always pretty amazing to find a new reason to put one of your idols up on an even higher pedestal” (136-7).

The closest we get to some kind of understanding is why a sixteen year-old boy in 2016 loves John Hughes—his mother was a film critic who also loved John Hughes. That, at least, is slightly more meaningful than ‘because nerd’. However, I suspect that this—as well as the fictional, similarly 80s-centric, Althena series Roxy and Graham love—is just an attempt to get millennial characters to somehow be as obsessed with the 80s as Gen Xers are.

Also, the John Hughes movies give rise to a very creepy take on his relationship with Roxy (who he assumingly wants to fuck): “But when she loved them, and she made me love them, it was, in a small way, like a piece of Mom was there—in her passions, which had found their way to becoming my best friend’s passions too.” A potentially sweet moment is rendered kind of icky when you’ve been browbeaten for 116 pages at how in love Graham is with Roxy.

This completely plastic, surface-level engagement with geeky pop culture carries through with the entire love arc, too. Graham never explains why Roxy is the object of his affection outside of 1) the mom thing and 2) she likes the things he does. One gets the sense that this is a relationship predicated solely on proximity rather than any actual emotional bond. Since this is literally the only driving force of the plot (since, as I mentioned, everyone just fucking loves this twerp), the utter lack of chemistry leaves me completely uninvested in the outcome.

Amidst all of this unnecessary angst are unwieldy and contradictory moral lessons which feel shoehorned in. And when I say contradictory, I mean just that. One is a random aside condemning “sneak attack politics” at Comic Con just six pages away from giving a textual tongue bath to the creator of The Chronicles of Althena for his injection of politics into his work (143). All art is political, and a convention celebrating that art will by its nature be political! How weird! Further, Felicia literally tells Graham that he shouldn’t have put Roxy (or anyone) on a pedestal/in a box, and yet somehow it’s okay to do to artists because… reasons?

And you know what? A lot of this could have been ameliorated if Graham had somehow just been able to learn and be better from this experience. After all, most of us have shitty understandings of human relationships growing up. We fix them on our way to becoming better. But the final chunk of the book doesn’t really sell that Graham actually grows as a person.

SPOILERS! HIGHLIGHT TO REVEAL!

Graham reveals his love for Roxy, at which point she freaks out. He spends most of his time mad at her for rejecting him. Eventually, his sulking bullshit somehow gets Roxy to plead for his forgiveness—that’s right, she apologizes for not wanting to be romantically involved with him. A girl who has been following him around the NYCC asks him on a date (and I’m sure she’s gonna be thrilled when she finds out that the entire time she’s been making googly eyes at him he’s been trying to get into his friend’s pants). So everything ends just fine, and Graham barely learns much of anything!

Oh, well, he did decide to create a loosely-autobiographical character for the comic he and Roxy work on. Only he’s angsty with a mysterious past because he hurt the girl he loved. So, yeah, he learned to do the most self-indulgent kind of pity-writing you can conduct when you’re a teenager.

This book has moments of legitimate heart buried underneath the constant drone of an unlikable main character who long ago swapped out positive personality traits for pop culture references. Outside of the main romantic arc, the novel struggles to find consistent themes and a moral heart to anchor it, only to end up flailing and contradicting itself. Unless you want just a steady stream of uncritical references to nerdy pop culture, you are better off finding something else.

< PREVIOUS ENTRY • NEXT ENTRY >

Advice • Fiction • Gaming • General Musings • Reviews