To the Moon: A Review

If you could rewrite your life completely, would you? Even if it meant that the only thing that would change would be in your head, could you bring yourself to forget everything you’ve ever done in favor of an entirely new life, lived in one moment before you die?

A game review? Unheard of! Spoilers? You bet!

On a whim, and because I’m a spectacular procrastinator, I purchased the game To the Moon on Steam yesterday. About three hours later, I had finished it, face still wet with tears. No, the game wasn’t so frustrating that I had to break it over my knee to be able to sleep at night. It was the compelling narrative which compelled me to marathon it. While, in the end, it isn’t quite as engaging as Lone Survivor is, To the Moon’s narrative satisfies on many levels without overstaying its welcome.

The story follows two doctors from the Sigmund Corporation, Eva Rosalene and Neil Watts, who are on their way to conduct an operation on a dying man named John. The procedure is not intended to save his life, however: the Sigmund Corporation specializes in making patients essentially re-write their entire life’s worth of memories in order to fulfill one dream. Obviously, nothing in the real world changes - but the patient dies believing that, against all odds, they triumphed.

Much like Eternal Sunshine on the Spotless Mind, the actual “science” behind this process is functionally irrelevant to the story. The more important aspects lay in the characters and events. At its core, To the Moon is a romance story played out in reverse and is far more effective than a lot of other media in how it engages with its audience. We already know the ending to the story: John’s wife passed away a few years ago, and he will die in a few days. The destination has been established, but the journey to that point is full of wonderful moments of discovery.

That isn’t to say that there isn’t a lot of pain to be passed around, however. Due to the way the plot is framed, the doctors must travel around a fairly confined ‘memory’ of John’s, finding enough things that trigger recognition in their patient to unlock a memento which gives them access to the next memory. If that seems difficult to comprehend, it really isn’t too hard to grasp when the game presents this information to you. It all seems perfectly logical to the player and, most of the time, anyway, the various items and events are fairly obvious.

Anyway, since each memento is tied to a fairly significant event in John’s life, expect to have to deal with quite a bit of tragedy. His relationship with his wife, River, is pretty bad toward the end. A combination of a mental disorder and an unknown “something” that John did combine to fuel a compulsion to endlessly make origami rabbits. As you travel further back, you see moments of despair and moments of joy.

As time goes on a more and more is revealed about John and River, and you experience firsthand a love story that starts strongly and ends with a widower wanting to purchase a new life, you at times forget that you’re controlling two doctors who have to go and systematically wipe out these memories. Part of the story’s biggest strength is that John never comes across like a bad guy, even though his final wish in life is to basically undo everything he’s ever accomplished. He, himself, doesn’t even understand the compulsion – he just knows it’s something he wants to do. In effect, his desire doesn’t stem from selfishness or malice at his sick wife, it comes from something much deeper.

Toward the end of the first act, it becomes apparent that there’s a particularly nasty memory in his childhood that John can’t quite remember. This event effectively blocks off the developmental years to Drs. Rosalene and Watts, making it so that the machine they use can not rewrite the patient’s experiences in any substantial way. Coaxing the suppressed memory free is the major thrust of the second act. Beyond that, the story picks up pace, tearing through the last third very quickly. This is not a bad thing - in fact, the pacing of the second and third act is probably the best for what the game maker is trying to accomplish.

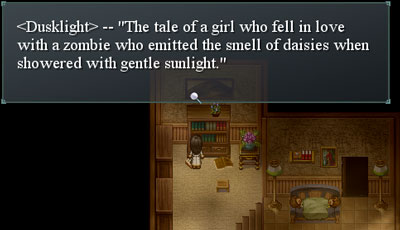

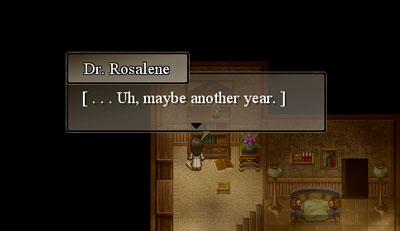

You know what this scene needs? To be horribly depressing.

The problem with discussing this game’s story is that it’s so good that mentioning even minor plot points seems almost unfair. It’s a powerful experience that everyone should be able have without it tainted. Even people who don’t play games should be able to get a lot worth out of the narrative quality of To the Moon. I strongly believe it to be a much better love/romance story than anything that has been produced under that genre heading for a long, long time.

Other elements of the game are equally effective. The graphics, despite being simple 2D sprites, are still gorgeous. The little touches on the characters, especially Dr. Rosalene and River, give a lot of personality using graphics which are not nearly as elaborate as 3D renditions. Things like River avoiding eye contact really draw out a lot of emotions, despite the cartoony atmosphere.

Honestly, the only fault would be the fact that Dr. Watts, hidden behind glasses, isn’t nearly as emotive as other characters. And it's certainly not through lack of trying, what with his wild gesticulations. But the sad fact, though, is that while the other characters are super-emotive because of their eyes, Watts just doesn't communicate as well with the audience. It doesn’t help that his personality makes me want to smother him, too. By the time the ending credits rolled, though, I started to appreciate his presence in the narrative.

Music is arguably the most powerful element of the game. The game’s soundtrack, created by Kan Gao himself, fits everything perfectly. Each track elicits an amazing emotional response, even when it’s been excised from the game. From the hauntingly beautiful opening theme, to the sad-yet-hopeful For River, to the smugly-titled-yet-unsettling Warning (AKA Best Track Ever), Kan Gao proves himself as a master of manipulating emotions. The moment Laura Shigihara provides vocals for John’s new memories is so powerful, it will sear its way into your brain. A previously mentioned track, Warning is especially powerful, reminiscent of John Carpenter’s The Thing, which itself is close to the human heartbeat.

Suffice it to say, the combination of graphics, music, and narrative work together to create a beautiful, powerful story. Even though most games let you play as a human being, a lot of them fail to deliver this kind of humanity at this level. The love story between River and John feels real, not because she’s a woman and supposed to be with the protagonist, like other stories. But because they’re both flawed people who, despite their inabilities to communicate toward the end, still love each other more passionately than a lot of people, real and imagined. It’s such an amazingly sweet story, made all the more tragic that, even in the fictional universe it occupies, the end result is entirely fictional.

But it’s not all positive. The game’s biggest strength is its narrative, to be sure. Its biggest weakness, sadly, is being a game. I don’t mean that in the Daikatana sense of being nigh-unplayable on first release. I only encountered one bug (a persistent one, at that), but that’s not really an issue. What is an issue is purchasing a game and not getting one.

The big problem is that there’s no ‘lose’ state to speak of. What I mean by that is that it’s entirely possible to ‘win’ the game, but it’s the same sense as ‘winning’ a book by completing it. There’s only two forms of player interaction outside of basic exploration. The first is unscrambling a memento, which is accomplished by taking anywhere between a 3 by 3 to 5 by 5 grid of an object and unscrambling it. There’s a minimum number of moves needed to solve each puzzle, but it’s never made clear what – if anything – achieving that accomplishes.

Later in the game, Dr. Watt runs through a gauntlet to stop something bad from happening. At this point, you shoot potted plants and zombies (don’t ask) while darting between spikes. The problem is that, although narratively speaking, you need to hurry, I don’t think there’s a whole lot stopping you from just letting the game run during this scene. I could be wrong, but “it’s a video game, so I run to the right because that’s what I do in video games” is hardly a good enough excuse to introduce a gimmick never to be touched again.

Outside of these instances, there’s very little to do outside of the game that isn’t mandatory exploration. There’s very little, if any, extra flavor text to help draw out the world. And that’s a shame, especially because the environments have the potential to be very richly detailed with text if the creator chose to do so. What this all leads to is that this isn’t really a game – it’s an effective story told using the trappings of a video game as a narrative tool.

I suppose this could have been alleviated by either eliminating the puzzles and replacing it with a branching choice: for every memento, you have three separate choices to make for leaping into the next memory. Your job is to use the clues you gathered to unlock the memento to figure out which memory is the appropriate one to jump to. Although there’s not necessarily a fail-state here, either, it’s a lot more narratively focused than playing a version of Othello where the purpose is to make the whole board one color. Plus, it gives the player the illusion of having an impact on how things proceed.

Another possible technique would be to have rudimentary battle-sequences, such as those found in early JRPGs. You wouldn’t need too much in the way of swords and sorcery, either. You’d basically have the two doctors work together (or by themselves) to figure out how to eliminate the mental threat by, once again, utilizing what you’ve learned about John in the present stage.

But I guess what’s really problematic about all this is the varying level of interactivity between the game’s separate acts. The first act, with the silly puzzles, suffers a bit from pacing because you’re basically reading an amazing story and then called out of the room every five to ten minutes to do something of little consequence. The next two third of the game are completely devoid of anything approaching this with the exception of the short Dr. Watts vs. Zombie section I mentioned earlier. Honestly, I’m not quite sure how I would even go about suggesting how to alleviate this, other than by just forgoing the attempts at being a game altogether. Kan Gao had a clear and incredibly strong vision for the story, but I think other entries in the series should perhaps focus more on eliminating the puzzles – if for nothing else, then for the pacing issues.

I think the best way to summarize this point is by briefly deferring to another reviewer. When discussing Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, Yahtzee of Zero Punctuation states that, when the game proudly proclaims to be a “Psychological Horror Experience,” it only gets “Experience” part right. This, in and of itself, is not a bad thing. I loved Shattered Memories to pieces, even if the only “game” aspect of it was running around like a crazy person and the “fail” state was the equivalent of having a narrator go “Whoops, that’s not how it happened,” before flipping back a couple of pages to try again.

In other words, being long on experience and short on game is hardly a bad thing. And, in the case of To the Moon, it is an experience which completely makes you ignore any gaming shortcoming it may have. It’s enjoyable, has moments of genuine warmth and humor. It will make you think and make you cry (unless you are a heartless human being who routinely kicks crippled puppies into traffic). It’s a game for both new and old players, provided that modern gaming hasn’t completely soured you to retro styles. No matter what, if you give it a chance, there’s a really good chance you will be satisfied. In the end, that’s something that I think we can all get behind.

And Dr. Rosalene is now my favorite character ever.

Related Content

< PREVIOUS ENTRY • NEXT ENTRY >

Advice • Fiction • Gaming • General Musings • Reviews